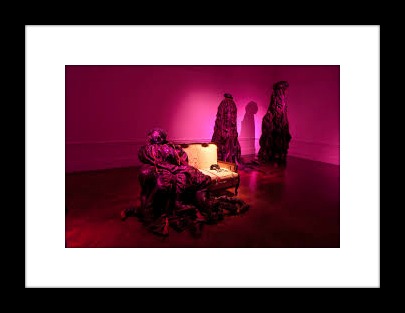

(Nicolas Hlobo, Izithunzi (2009). Rubber inner tube,

ribbon, organza, lace, found objects, steel, couch, variable dimensions.

Monument Gallery, Grahamstown.)

South Africa is heavily weighed down

with issues most of which are overshadowed and ignored, while others, such as

race and racial bias, are constantly and almost obsessively prioritized because

of our history with Apartheid. Zanele Maholi and Nicholas Hlobo are two artists

who are notorious for their works in broadening perspectives on concerns that

are often overlooked by society, such as gender inequity and homosexual

discrimination. In this essay I explore how their artworks: Izithunzi (Fig. 2),

Miss D’vine II (Fig. 3), Stanley Mabena 11 (Fig. 4) and Nando Maphisa and Mpho

Sibiya, Sasolburg (Fig. 5), define gender in the post Apartheid South Africa.

Western society has long battled the

stereotype that women are inferior to men and despite advances in western

feminism gender bias is still a major issue in African and Middle Eastern

cultures. Together, Hlobo and Maholi have a broad collection of artworks that

explores and exposes how black men and women are repressed by their culture

because of their gender and sexuality. This occurring in spite of the fact that

the South African constitution does not condone gender or homosexual

discrimination. In fact the South African constitution embraces every citizen

no matter their race, gender or sexual orientation. Each individual has equal

human rights, and yet there are still those that defy the constitution by

resorting to hate crimes and corrective rape to such an extent that when

reported to the police these injustices are not taken seriously. Because of this

it is dangerous to publicly admit to being homosexual or transgender in a

post-apartheid South Africa.

When looking at Nicholas Hlobo’s installation

entitled , Izithunzi (Fig. 2), the

work at first appears to be completely arbitrary, but it is essentially

swimming in symbolism. Izithunzi is one of two installations that complete the

piece known as Umtshotso which refers to the rituals of entering adulthood in Xhosa

culture (Gevisser 2009: 2). It portrays the exploration

that comes with age and the consequences that come with wanting to be

mature before your time. Izithunzi (Fig.

2) is made up of eight figures scattered across a dark room with an ominous red

glow cast over the group. Izithunzi means shadows (Gevisser

2009: 3),

which in itself is awash with meaning. The shadows of leaving our innocence

behind, the shadows we hide behind when society does not accept us for who we

are and the shadowy thoughts that come with adolescence, especially those

dealing with the issues of discovering a different sexual identity to what we

have been brought up with.

The

figures seem to resemble a Halloween party with their jellyfish, pumpkin and

ghost like shapes. The idea that the

figures are gathered for a party draws to the original idea of the traditional

Xhosa party undertaken before adulthood. The costumes however, ignite a deeper

meaning and a comment on Hlobo’s own sexuality. With the idea in mind that

being openly homosexual in a post-Apartheid South Africa is dangerous the

result is that many hide their sexuality behind a costume, pretending to be

something they are not and often dealing with the idea that society presses on

them - that they are unnatural, that they are freaks. While those that oppress

them are in actual fact the freaks and the monsters of society. Each figure is

constructed of materials rife with meaning. The rubber inner tubing symbolises

the hardened texture of masculinity as it can refer to a condom and is quite a

tough textile. A direct contrast to the rubber is found in the use of delicate

feminine details such as, lace, organza and ribbon. These textiles connect each

figure, thus representing the unification of masculine and feminine whether

through intercourse or homosexuality an ambiguity is created that challenges

assumptions on gender stereotypes (Gevisser 2009:2).

The aboutness of my chosen three photographs

taken by Muholi is similar in context Izithunzi. Miss D’Vine II (Fig.3) is a

photograph of a man dressed in feminine attire. The subject matter and the

photo itself is not as serious as her other works but it is effective in highlighting

the bridge between masculine and feminine.

In her photograph entitled Nando

Maphisa and Mpho Sibiya, Sasolburg(Fig. 5), their clothing has been

thoughtfully chosen as it is the uniform of a sangoma, which is an ambiguous

position in her culture. With MissD’Vine II (Fig 3), the gay male in women’s

dress associates with drag, transgender and role-play. It can however be argued

that she is imitating a preconscious stereotype with the picture while the red

shoes remind me of Dorothy from the wizard of oz and her ruby slippers that

aided her in defeating the wicked witch. Is that not the outcome the activist

in Muholi desires? To defeat the wicked who abuse and mock a person because of

their gender or sexuality?

The aboutness of my chosen three photographs

taken by Muholi is similar in context Izithunzi. Miss D’Vine II (Fig.3) is a

photograph of a man dressed in feminine attire. The subject matter and the

photo itself is not as serious as her other works but it is effective in highlighting

the bridge between masculine and feminine.

In her photograph entitled Nando

Maphisa and Mpho Sibiya, Sasolburg(Fig. 5), their clothing has been

thoughtfully chosen as it is the uniform of a sangoma, which is an ambiguous

position in her culture. With MissD’Vine II (Fig 3), the gay male in women’s

dress associates with drag, transgender and role-play. It can however be argued

that she is imitating a preconscious stereotype with the picture while the red

shoes remind me of Dorothy from the wizard of oz and her ruby slippers that

aided her in defeating the wicked witch. Is that not the outcome the activist

in Muholi desires? To defeat the wicked who abuse and mock a person because of

their gender or sexuality? Her reference to

gender ambiguity continues in her work entitled Stanley Mabena 11 (Fig. 4).

While he has a male name his breasts are bigger than a man’s should be while

smaller than the average females, his face is feminine but he appears to have

recently shaved too. As he leans more to the female side despite the fact that

he is male it creates the appearance of vulnerability. In many of Muholi’s

works masculinity resembles the harshness of life while the feminine is

portrayed as defenceless. Looking again at Nando Maphisa and Mpho Sibiya, Sasolburg

(Fig. 5), she has photographed a same-sex couple who are dressed as sangoma’s

which links to how the position is one free from gender bias and yet, they are

declaring themselves lesbian too, which despite this occupation goes against

their culture and is recognized as taboo.

Her reference to

gender ambiguity continues in her work entitled Stanley Mabena 11 (Fig. 4).

While he has a male name his breasts are bigger than a man’s should be while

smaller than the average females, his face is feminine but he appears to have

recently shaved too. As he leans more to the female side despite the fact that

he is male it creates the appearance of vulnerability. In many of Muholi’s

works masculinity resembles the harshness of life while the feminine is

portrayed as defenceless. Looking again at Nando Maphisa and Mpho Sibiya, Sasolburg

(Fig. 5), she has photographed a same-sex couple who are dressed as sangoma’s

which links to how the position is one free from gender bias and yet, they are

declaring themselves lesbian too, which despite this occupation goes against

their culture and is recognized as taboo.

Hlobo and Muholi collect the emotions and

problems that South Africans face on daily basis in their art. They archive

them in a collection that can be viewed by the world as if saying, you

wanted to hide it, but this is the truth. This is what is happening! Let’s do

something about it. They collect evidence and histories, each photo is a story,

and each artwork is figurative slap in the face to a nation that needs to wake

up. While seemingly arbitrary at first, they are in fact memories of trauma and, invested with meaning. An objection to those who condone

discrimination of any kind and a plea to our government. Clearly the artworks

discussed proclaim that we still fight an apartheid in a post apartheid South

Africa, one of gender discrimination. Proving that we are not as equal in this

new order as we had hoped.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.